The Subaru banged over the washboard road, headlights sweeping over plains of scrub and yucca. 35 degrees on the car thermometer. A green hint of dawn growing in the eastern sky. The stars began to fade. It would be another day of heat and dust.

Our path was not upon that desert plain, but beneath, in the recesses of Bluejohn Canyon. There we would pass through shadow and icy pool, squirm along narrow passages in the sandstone. Blue John gets its name from one of the many outlaws that hid out in central Utah’s Robber’s Roost during the frontier days. It’s also the place where a young adventurer named Aron Ralston famously dislodged a boulder onto his arm back in 2003, amputating his arm with a pocketknife in order to escape.

Not in our plans. We wanted to descend the same way Ralston went, headed north within the east fork of Bluejohn. But where Ralston continued down canyon with the intention of joining with the larger Horseshoe Canyon, we would split off early onto the main fork and ascend back to where we started. By cutting off this last section of canyon (and hopefully not any arms) we would have about fewer miles to cover than Ralston had planned, nor the miles of mountain biking that he shuttled before he even got to the canyon.

The sun came up to find Andrew, Jon and I still grinding along the dirt track. Though we had about 20 miles to cover, the rough roads in Robber’s Roost made sure we wouldn’t cover the distance in less than an hour. That same merry sun shining down on us now was bound to climb higher, and then sink to leave the world dark again. Hopefully we’d have made it through the canyon by then.

We passed a curious sign that read something to this effect: “These are not your cows! They are not wild animals! Leave them alone!”

I tried to imagine the provocation: some prankster canyoneers taking a break from their adventures to tip cattle? Neo-hunter-gatherers lashing bovines to the Thule rack on the way back to clans in Boulder or Taos?

We parked at the Granary Springs trailhead. An ominous ranch shed guarded the dusty lot. Someone had stenciled the Motel 6 logo onto the corrugated metal siding.

A couple hundred feet down the trail we came across a herd of beefs (not our cows!) grazing near a galvanized water tub, sun glinting off their dusky hides.

“Should we be careful around them?” Jon asked.

“Nah, they should be fine,” I said, grabbing a dirt clod to fling at the beasts.

“Fuck off!”

I didn’t expect anyone to take it personally, but the one that swung around, front hooves in the air seemed less than amused. The couple thousand pounds of bulk and trampling hooves made a strong case that perhaps I, not he, should be the one to take a hike.

I apologized. I guess that sign was meant for punks like me.

We walked north along an arroyo with cattle droppings and hoof prints all over the place. It didn’t seem likely that the biological soil present in Arches and other pristine parts of the Southwest could have survived under the trampling here.

Our course bent northeast toward a notch in a ridge, affording us a view of the snowy flanks of the La Sal rising in the distance. The next mile descended into a flatland, populated with desert scrub and mined with innumerable prickly pear cacti hiding in the grass.

I stepped carefully in my water shoes. No hiking boots today — not when plans called for wading, possibly swimming icy pools at the canyon bottom. I did wear thick socks on the inside to prevent blistering and for extra insulation.

The sock/water-shoe combo is just one example of how I’m a leader, not a follower when it comes to fashion. Take the boxers I wore outside of my wind pants. Not only were they glamorous, the plaid cotton underwear also covered the gaping hole I’d ripped in the seat on the way through Chambers Canyon last year. They would lend extra padding against the rough canyon walls — at least that’s what I hoped.

Other clothes included my fleece layer, windbreaker and space blanket for staying warm; cookies; first aid stuff; and the camera around my neck. Add the climbing shoes and harness for good measure. Oh, and let’s not forget the gallon of water sloshing inside an Arizona Iced Tea jug.

All this stuff came out to a good-sized bowling ball in my bag, a bowling ball that I would get to lug up and down the slots.

But why should I complain? Andrew and Jon traded off the burden of my enormous dry bag, stuffed with 200-odd feet of Andrew’s climbing rope, their climbing gear, clothes water, Gatorade and food. I still hadn’t fixed one of the straps that I’d busted biking through the northwest, leaving them to improvise a way to secure the weight onto their backs.

We hoped that our loads weren’t too cumbersome for the narrow canyon ahead of us, but that we would also have enough to make it through fed, secure, watered and warm.

As far as introductions go, Bluejohn was unimpressive. Desert runoff had carved a gentle V-shape into the sandstone, about 50-feet deep and at a gradual angle. I only had to put my hands down once on the descent, and only because there was some loose scree.

The three of us began an easy hike down the sandy canyon bottom. There was mud here and there, a couple of puddles. The first couple of these were easy enough to walk around, but as the canyon narrowed, we found ourselves hopping from rock to rock or bracing our feet and butts against the walls so that we could scoot over with dry feet. At one point we simply walked above the center slot until we got back to the dry sands.

We weren’t going to get many more options like that in the miles ahead. Indeed, it is the nature of these canyons to limit the explorers’ options, sequester then between walls so that they can only move up, down, forward. The option of turning back became less and less the move we down-climbed, evaporated at our first rappel.

The canyon bottom became a series of brownish pools. The walls became far enough apart that we could no longer climb above the water. We began a foot-numbing trod from one pool to the next, sinking knee to thigh deep. Only a couple of hours of sun could have reached down here each day, leaving the water incredibly cold.

I thought of the canyon guide, which said to expect deep wading or swimming in the canyon ahead. A couple hundred yards of this stuff above waist-level would be definite hypothermia risk.

Meanwhile, the walls on either side of us were at least 100 feet above our heads now — straight up, smooth, unclimbable. The sun retreated behind the red rock. Our world shrank into a tall, narrow slit, defined by curves of water-carved stone. We would need to be as adaptable as the water that rushed through — widening ourselves to fill the vacant spaces and climbing higher where the canyon narrowed.

Another passage of thigh-deep water took us to a 25-foot drop above a shadowed pool. How deep? Impossible to tell in this light. A bolt in the left-hand wall offered a place to secure a rope.

We took a quick food-break on the narrow ledge, watching a chunk of cow turd float listless in the water. I volunteered to make the first descent. Andrew worked the rope through the bolt and lowered it down to the water. I put my harness on, fit the rope into my belay device and stepped into the edge. I eased myself down gradually, preparing to unclip myself quickly when I reached the water.

“It would really suck to drown here,” I said.

“I hear drowning’s not such a bad way to go,” Jon said.

“Really? I hear it’s about the most painful way to die imaginable,” I said.

The wall went inward right above the water, causing me to swing around to the left. I eased myself part way into the water then unclipped myself. The pool was only about waist-deep, but that was deep enough to freeze my ass.

I lurched along the slippery rocks on the bottom with my jaw clenched in a rictus of cold. There was about 20 feet to go before I reached the end of the pool. I got out and watched shivering as Andrew and Jon prepared to descend. They would have to stay in the water longer in order to retrieve the rope. I got to move further down the canyon to a patch of sunlight.

We regrouped dripping wet, with Andrew bitching that he was soaked in shitwater. We all were.

There was more to come.

We sloshed our way through knee-deep puddles until we came to another ledge. A side canyon came in here, leaving a long pool of water stretched along the path before us.

First we needed to get down there. This drop was only about 12-feet, but there was no bolt in place for rope. We would have to be our own anchors. Jon and I braced ourselves against what purchase we could find up top and held the rope for Andrew as he climbed down. Then I held the rope for Jon. Since there was no one left to hold the rope for me, I slid a short ways on my backside, then got a foot down on Andrew’s shoulder where he was braced between the canyon walls.

I thought of Ralston going down the canyon solo wondering what he did when he got here. A natural anchor? Did he figure out a way to downclimb, or did he ease himself down as far as possible and then jump for it?

The channel of water at the canyon bottom was muddy brown — impossible to judge depth again. The water stretched out for 50 feet in front of us and disappeared around a corner. The walls were narrow enough that we could boogie above the first section, but alas, they widened out again. A huge boulder wedged between the canyon walls prevented anyone from continuing the route above the water. Either we were going back, or we were going in. Except we couldn’t go back. The two ledges we’d rappelled down had nixed that option.

Andrew clambered in first. It was a little over waist-deep. Jon and I stayed up on the walls, listening to a stream of splashes, shouts and profanity fading down the canyon. Something out of my sight provoked an especially strong oath. I wondered what the obstacle was.

I’d be the next to find out.

I climbed down to the water and immediate misery. Jaw clenched, I started the frozen march through the pool. With every step, I gifted a little bit more of my heat to the murky waters. I snorted and swore. Soon I was just making a series of grinding, chortling noises.

A mass of logs had wedged between the canyon walls a couple feet above the water’s surface. I pushed myself past as best I could, wanting to get out of the water as soon as possible.

Andrew was standing on dry land at the other end, laughing at me. I was laughing too, then swearing more.

I surged out of the water and immediately started putting on layers from the dry-bag. My jaw was clenched tight enough to hurt, mind starting to go reptilian from heat loss.

We were lucky enough to have some sun patches nearby, where we warmed ourselves as best as possible before moving on.

The canyon opened up. Soon our path was a wide-sandy bed in full sun. I was aware of the warmth outside me, but it would be a while before any of it reached the chill in my core.

Even the canyon walls, which I’d assumed to be impregnable, seemed to have a few slopes that might have been gentle enough for us to escape. We were still committed though. It was encouraging to take lunch on a warm slab of rock. The next couple miles were easy going on the sandy bed, with plenty of room for us to enjoy the tall red-rock formations hundreds of feet overhead. This part may have been easy, but not many people would make it down here to enjoy it.

An intersection brought us to the main fork of the canyon and our path out.

The first mile was the same pedestrian hike over sand, the walls slowly moving closer. Whiptail lizards darted here and there, racing over vertical canyon walls with incredible agility.

“Whoa! Hey! Check it out!”

Jon pointed to a two-foot rattler right next to my footprints, buzzing like a cicada. It hadn’t been too likely to bit me though, not with its head stretched around a whiptail lizard it had caught. The snake slithered under a rock where it watched us from the shadow, tail still buzzing, still trying to finish the lizard in its jaws.

No, we weren’t in a great place for a snakebite victim.

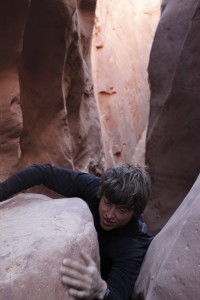

Soon we were scrambling on the walls again, shimming over pools. The canyon floor suddenly rose into a steep climb up a 10-foot ledge where a chockstone the size of an ATV blocked the path. Jon went first, chimneying off the canyon walls until he was a few feet off the ground and the scrambling the rest of the way up the ledge. Andrew and I waited as he grunted and clawed his way beneath the boulder.

“I don’t think you guys can make that,” Jon told us. Since he was the skinniest in the group, I weighed those words. The alternative to squirming under would be an attempt to climb over the boulder. The large drop off made this idea less than appealing.

I started chimneying further back than what Jon had started from, intending to go up the walls diagonally to the top of the ledge. The walls had other ideas, however. I found I could keep myself up better, by going up high where the canyon narrowed. Soon, I was on level with the top of the chockstone, 15 feet above the ground, suspending myself with friction.

“I think I might try to over this thing,” I said.

Doing so required me to twist and use some fancy footwork, cheap water shoes smeared against the rock. While I wriggled, inch by inch to the chockstone, I found the walls getting wider again, too wide for me to support myself. But the chockstone was right there. All I had to do was put my foot on it, trust that it would stay in place as it had doubtless stayed in place through the millennia, that this was not my unlucky day. Ralston had trusted a stone like this one and had it come crashing down on him.

Downclimbing at this point would have taken colossal energy though. I had already exhausted myself getting this high. What if I tried to go under the boulder and found out Jon was right and it was too tight for me to get through?

I put a hesitant foot on the rock, bracing as much weight as I could on the walls. Nothing moved. I put more weight down, then moved to the stable ground on the other side, quick as possible.

Andrew took a lower route than I, but he too went over the rock.

The walls narrowed and the floor went up. We chimneyed a couple dozen feet and kept working our way south. The canyon took a 90-degree turn, presenting us with abrupt 12-foot climb up a sandstone face. A much larger drop waited on the left side. I went first, finding a decent handhold on my right and a good place to kick out my legs on the wall behind. I froze briefly on the wall, felt someone grab onto my feet.

“No. I got this,” I said like I actually believed it.

I curled my fingers over a tiny ridge of rounded sandstone at the top of the ledge, used it to pull myself the rest of the way.

The other two passed the bags to me, then readied themselves for their own climbs.

Jon had more trouble with the handholds. I got ready to grab him from above if necessary. This meant kneeling in a shallow pool (thankfully, the water was warmer than in the first canyon) with my knees against the rock to get a decent brace. Jon froze with the top of the ledge at about shoulder height.

“Grab my hand,” I said.

“I’d just swing you over the edge,” he said. Maybe he was right.

He went down for a second attempt. I fixed myself deeper in the pool to get prepared.

And by prepare, I mean that I got my camera out, ready to shoot that dramatic moment when he got to the ledge.

Jon seemed a bit surprised to see my camera lens in from him instead of my outstretched hand.

“Hey. I need some help here.”

I put the camera down and grabbed him. Guess I’m not New York Post material yet.

Andrew was next. He too hesitated near the top, was probably going to make it, but Jon had already grabbed him. I snatched a pant leg and we flipped him out on the ledge.

We moved on to an even longer climb, to another ledge beneath a boulder. This time, we had to carry the bags with us. I threw the dry bag in front of me, letting it wedge in the canyon in front of me. The walls widened again, so I climbed on without the bags and Andrew climbed above them, passing them to me by hooking them with his foot. The three of us gathered beneath the enormous rock, trying to figure out what to do next.

The walls above the boulder were too wide to chimney over it. I decided to try getting past on the left side, even though I wasn’t sure what I was going to do after I got halfway up. I scooted between boulder and canyon wall, then reached over the top to a beautiful handhold.

The final climb was a 20-foot ledge. I went last this time, watching Andrew and Jon clamber up a corner between the walls. I scrambled after them, climbing out from the dark, back into the world of cowshit, blue sky, dust, sunshine on my face.