The break in the road was far less dramatic than what I had envisioned. The only thing that kept motorized traffic off the eight miles of asphalt leading to Olympic Hot Springs was a minor washout, hardly more than a dozen feet across, carved by an errant channel of the Elwha River. A small wooden bridge over the gap, made it easy enough to cross and, apparently, Park Service vehicles were already using it to conduct their business. Nonetheless, that gap in the road, cut off civilian traffic to the springs — unless, of course, they were motivated to get there without a car.

I left my car back at the Madison Falls parking lot, where the Park Service had barred the road, and started down the pavement, backcountry camping permit attached to my pack. After going a few paces at a walk, I fell into a light jog, then thrust my chin forward and started running.

This was the first time I’d tried camping with a backpack light enough for me to run with. Items like a sleeping bag, tarp, food and first aid supplies added weight on my shoulders, but the burden was a manageable one. I was pleased to see myself moving much faster than conventional hiking speed.

Crowds of people of people strolling out from the parking lot diminished rapidly as I put miles down. Here and there, and odd biker cruised along the pavement.

The murmurings of the Elwha drifted through the trees, sounds that would no doubt have been drowned out by the din of auto traffic a year earlier. There was no exhaust in the air, but a stimulating tang of sun-warmed pine needles refreshed my spirit. For all my scattershot planning, second guesses and doubts, it was good to actually be out there doing the thing.

I would run 10 miles and climb 2,000 feet, then camp near the springs with the small provisions in my pack. The next day, I would log about 22 miles over a five-thousand foot mountain ridge.

I stopped on my fourth mile to walk out on the remains of the Glines Canyon Dam. The abandoned road had already lent a post-apocalyptic theme for my trip, but this was something else.

A walkway led out onto the 210-foot span, then ended abruptly for a view into a chasm where the rest of the dam used to be. The milky-blue Elwha river ran unencumbered beneath the gaze of its former captor. Rapids thrashed out against the stone walls and churned in a confusion of rapids downstream.

What disaster had destroyed this mighty dam? No disaster (depending on who you ask) but a public project to restore the river and bring back salmon. The Park Service signs around the site explained the work, the largest of its kind in US History.

Since the Elwha Dam construction began in 2010, the Elwha has been a dammed river. The Glines Canyon Dam followed in the 20s, providing the electricity that helped run the mills in nearby Port Angeles, Washington. The dams also blocked salmon access to 70 miles worth of prime salmon spawning ground. Thomas Aldwell, the Canadian-born dam financier, did not bother putting fish ladders in either of his dams. Even if there had been ladders, the fact that the dams held back sediment and drastically changed the river temperature was still enough to spell disaster for salmon and steelhead populations that would have used the river before. How much sediment? The volume is equal to the area of a football field multiplied by 2.25 miles according to the Park Service. A beach has reformed at the river mouth as the sediment comes down the current, and it is even replenishing Ediz Hook, the narrow of land spit that forms Port Angeles’s natural harbor. The Hook has become a popular fishing spot in the wake of dam removal.

When the dams went up, they dealt a hard blow to the salmon fishing livelihood of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, which lives near the mouth of the river. Not surprisingly, the Klallam were a major proponent of dam removal. Congress approved the process with the 1992 Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act, signed by George H.W. Bush.

It took until 2011 for the last of the Elwha Dam to come out and longer for a floating barge to chip out the Glines Canyon Dam. In 2014, the last 30 feet of the structure went down in a blast of dynamite.

Life is finding its way back to the river. The salmon are beginning to re-find their old spawning grounds now, thanks in part to help from humans, who have released the tiny spawn upstream of the dam sites so that they would imprint and later return to these habitats. On a recent kayak trip down the Elwha rapids, I got to see the artificial log-jams along the river that slow and cool the currents, making life better for returning salmon.

More human effort to realign the human-scarred landscape included the willow, salal, black cottonwood and numerous other native species workers had planted along the edges of the gray siltscape that marked the former Mills Reservoir to my south.

After a century of imprisonment, however, it should be unsurprising that the river should lash out a bit upon release. Hence the washed-out section of road, which made the traffic on the Hot Springs road a no-go.

The landscape around me seemed more wild just knowing that there wouldn’t be seeing any families leaving the engine idling as they got out for a quick picture of it. I looked up to the snow on the peaks in the Olympic Mountains and knew it was time to start running again.

My calves got a nice workout as I knocked out 2,000 feet of elevation in a couple miles. I stopped to enjoy a lookout over the Straight of Juan De Fuca and distant Vancouver Island.

The road ended at a National Park trailhead. No mountain bikes allowed beyond this point. Everyone was now foot traffic like me. Other notices remarked that a suspension bridge along the trail was considered unsafe, also that fecal coliform had been found in the hot springs (I thought all coliform was fecal, but yeah, nice way to emphasize that point.) The National Park Service still says no to weed, no matter what the laws were in Washington State. Uncle Sam set the house rules here.

The trail was easy running, with wide margins and the occasional ditch to hop. I spied a woman walking over the questionable suspension bridge, and decided to take my chances with it, even though I was a bit heavier.

The trail continued along an Elwha tributary and led to another bridge where I smelled the faint aroma of rotten eggs. Lines of rocks marked the springs, helping to shore up the water. The manmade walls were a far cry from the concrete, entrance fee and bath towel affairs that I’ve seen at commercial hot springs elsewhere. They were a small human improvement, and the damming seemed far less egregious than the toppled behemoths that had sequestered the Elwha.

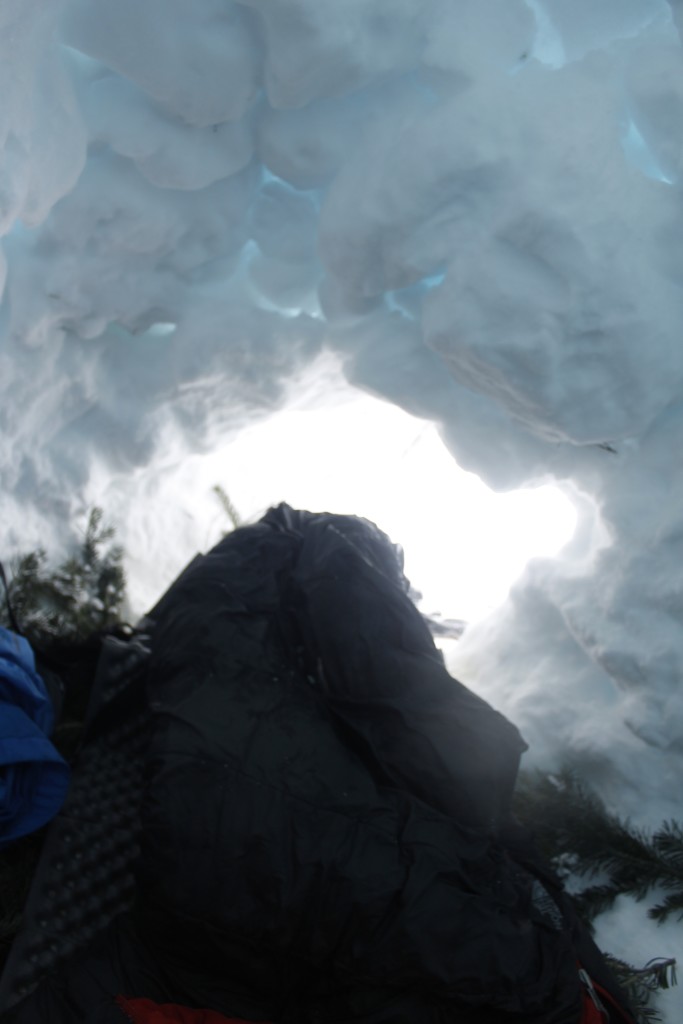

I explored tiny trails leading to secret springs, finally found a murky pool that was a way above the main trail. A bright blue line of mineral substrate issued from the crack in the rocks where the water fed this natural spa. Steam wisped upward from the dark mirror surface. I took my clothes off.

I put a foot in the spring. The water was scalding. Then, I dangled a leg in and waited until it seemed OK. I let the rest of myself settle beneath the murky surface.

Aahhhhhh. Not bad! Not bad at all!

Beads of sweat formed on my forehead as I gazed at moss-covered branches overhead and the blue sky beyond.

If I had no one else to share the spring with me I could thank/blame the Elwha again for taking out the section of road and limiting access. I’d heard from others that the springs were usually crowded during the summer months. Such crowds had likely brought the coliform contamination as bathers answered nature’s call near springs.

I made a mental note to use plenty of hand sanitizer before dinner that night.

Fires were not allowed at the springs campsite, but I hadn’t found out until I got there and I’d saved weight by not bringing a fuel stove in my backpack. There had yet to be a general burn ban in the forest. Nor did the prospect of cold pea soup crunch for dinner did not appeal.

I was determined to make the tiniest of fires, reasoning that done right, this would be more ecological than fossil fuel. I used mineral soil at the base of a felled tree as the fire sight, and built a fire pit of about six inches across using three large stones. Using a vaseline-soaked cotton ball as starter, I started a minute twig fire, that was nonetheless enough to boil water in a pot for soup.

Plenty of us use camping as a way to reward the fire bug in ourselves, delighting in how large we can build the flames from the available wood. It is a perverse application of American “more is better” mentality, where people think that the ability to squander resources makes it their right. Knowing that most people are going to strip large amounts of wood from the surrounding forest, it is no wonder that the Park Service would want to ban campfires at the site.

Some may call me an elitist scofflaw for excepting myself from the rules. I nonetheless took pleasure from trying to make the smallest, most efficient blaze and utilizing it to full capacity. I got plenty of warmth by getting close up to the flames. By the time the fire had burned itself out, I had scarcely gone through a few handfuls of twigs. I heated some more water on the embers and drank the scrapings from the pot.

Like the fire before it, my shelter was a small affair` . I strung rope between two trees and lay a short tarp over it. I carved out some stakes from twigs with my pocket knife. Sleeping bag and tent pad went beneath the tarp. Though the end of the bag stuck out from the end of the tarp, I’d planned for this by bringing an ultralight bivy sack to put the bag in. If it rained that night, I should be dry. I found a scrap of plywood nearby and used it as a wind block.

What the bivy sack did was it made me way too warm in the bag and that is why I woke up early that morning with plenty of sweat soaked through my sleeping bag.

Mountain peaks that had shone in the alpenglow the night before were now obscured in cloud. I considered that the trail ahead of me could be cold and damp. All the more reason for a morning fire.

I set up a pot of water for oatmeal. As the flames leaped, I held the wet sleeping bag as close as I dared to the fire, and was pleased to see much of the moisture evaporate.

I started running down the trail at around 7:45 am. The trail beyond the campsite narrowed and began taking me up a series of switchbacks on my way to Happy Lake Ridge. My water bottles were empty, I planned to fill up when I got to Boulder Lake which was still about 2,000 feet above my head.

I split my time between running and power hiking as I continued to gain elevation. After a while, I saw the “No Fires” sign, that meant that I had reached 3,500 feet. The trees were less dense then when I had started the other day, with large Douglas firs and Sitka spruce predominating.

I paused at Boulder Lake to filter water and eat second breakfast. The cold mist soon had me chilled and made me put on other layers. I realized that I didn’t have any gloves, but I had accidentally packed one extra sock, which I put over one hand. I wondered if I were really equipped to take on a mountain ridge, bound to be more exposed and colder than what I was dealing with. The trail beyond the lake looked not so well maintained, which worried me because I wanted to cover ground quickly to get back to the car by the end of the day. It would have felt defeating to turn around at this point, though, and I vowed to press on.

I started a brisk hike up a series of switchbacks before starting a brisk hike up to the top of the ridge. The trail was narrower here and the wet shrubbery slapped at my legs. I had to pause repeatedly to climb over and under fallen tree trunks. Spears of broken wood waited for my soles to slip on the slick bark.

More meadow-like areas waited at the crest of the ridge. The trees became scrubby dwarfs. Beyond the shifting clouds were hints of grand valleys and towering peaks just outside my vision. I ran along a rollercoaster of ups and downs, leaning forward to tackle the steep descents on gravel. I breathed easily, pushing, not straining, letting my feet turn over under the pull of gravity and for the rhythm of tiny footfalls to carry me down. The energy flowed over into the next rise, and then, I sank tiny steps into the hill, letting them bring me up to the top. Then down again. The trail cut along steep pitches, where a missed step could translate into a messy tumble through rock and briar.

I may not have been smiling, but my heart beat with the quiet joy of the moment. Trail running affirms the present tense, or at least it diminishes my awareness of past and future. I work on a micro-future of what will happen in the fraction of a second before the next footfall, how the torso should turn before the feet do, how to anticipate a landing with one’s entire body. Focus on these minute calculations helps me hold off worry, whether it is troubles in the past or anxieties for the future. I take simple happiness in flowing through the motions with my mind and body. Like the river below, I had (however briefly) unshackled myself.

A patch of snow on the trail, emphasized that I was in mountain country now. A couple miles later, I took a half-mile detour to run down the trail to Happy Lake, where contours of snow clung to the north face of the valley, bleeding into a small stream. The water was so cold that the first mouthful gave me brain freeze.

The clouds broke to the blue sky. A glaciated mountain ridge revealed itself in the distance.

The trail started going down. It would be about 3,000 feet of descent to get back to the paved road and then another 2,000 feet to the Glines Canyon Dam. I let myself begin turning the feet over.

I knew my quadriceps were going to hate me for going down the switchbacks at full tilt. Still, it was good training for them if I wanted to do more mountain running in the months to come. I ran with tiny steps to minimize the individual impacts on my knees.

The sheer pitch of the hill made it impossible for me to run with total abandon, and soon I felt the burning in the quads, which would render me a hobbling oldster for days later every time I walked down stairs.

The trees got bigger again. The scrub grew low and even in a verdant layer that looked like it had to have been manicured. It made me think of some twee victorian park. But I was the only one on the trail.

The twisted, orange trunks of madrona trees flashed by as I skidded down through the curves. Soon, I saw the asphalt line of the road. I got back on and pounded the remaining 2,000 feet to the Glines Canyon Dam.

Walkers and bikers strolled at their leisure along the closed road. I smiled and waved. Everyone seemed in high spirits. If they had been in vehicles they would have blown by me with waves of noise and exhaust.

They should keep the road closed, I thought.

Edward Abbey, famous road hater, would have approved, just as the dam removal would have been much to his liking.

In his book Desert Solitaire, Abbey proposes closing all national parks to personal automobiles, and that people go in on “…horses, bicycles, mules, wild pigs..” instead. He reasons that parks will seem far vaster and grander to people if it takes them more effort to get in than, say, pulling up to a drive-thru.

Abbey writes: “We have agreed not to drive our automobiles into cathedrals, concert halls, art museums, legislative assemblies, private bedrooms and the other sanctums of our culture; we should treat our national parks with the same deference, for they too, are holy places.”

I’m inclined to agree. Just to the east of the Elwha River, the popular Hurricane Ridge Road allows tourists to go mountain climbing in their cars. The shimmering snarl of traffic with the grumble of engines reverberating through the valley is a desecration.

Perhaps simply getting people into these places is worth the road building, the smog and the chaos of crowds. When I see the vast majority of these smartphone-equipped people hardly straying a mile from the machines that brought them in, I wonder how much they are appreciating there surroundings, and how much they are just sucking down the experience like so many Big Gulps from the drive-thru window. Is it a meaningful experience for them, or just a momentary sugar rush, an audiovisual novelty? I see little difference between looking at something from the RV window and seeing it on a screen.

Alas, construction on the broken road is going through as I write. Now completely closed off to civilian access, it will remain off limits for an eight-week period. Then, the asphalt river will reopen, and visitors will be able to migrate back up into their territory.

With the dam broken and the road back under construction, the end result seems half right.

As I ran along, a mountain biker called out to me.

“Hey, didn’t I see you here yesterday?”

He had biked to the trailhead yesterday and hiked the remaining two miles to the springs. He’d liked it so much, he was doing it again today. Bombing back down the 2,000 feet of twisting turns on the empty road was one of his favorite parts of the trip — he clocked himself around 40 miles-per-hour.

When he got to the top of the hill, he would hike the remaining two miles into the springs.

“It’s nice having them without the crowds isn’t it?” I ventured.

“Are you kidding?” He said. “That road washout was the best thing that’s ever happened out here!”