What was amazing about my homemade pulk sled was that it worked.

I’d dripped ski wax onto the bottom of the kid’s sled for maximize glide. From there, I loaded on jumbo snowshoes, a monster backpack, sleeping bag and separate dry bag full of food. I lashed ‘em all together with cam straps, affixed cam straps to ski poles, affixed other end of poles to a carabiner on a belt around my midsection.

When I moved on skis, the sled followed. Nothing fell off or skidded into the snow.

I skied east on the snowmobile trails toward Slavonia, a trailhead in the Zirkel Wilderness, which was on the way toward Big Agnes. This 12,000-foot mountain had become an obsession of mine for a couple of weeks. There were the usual symptoms: staring at the topo map, figuring routes, squinting at the distant mountain from the groomed ski trails.

Now, I was skipping out on a fun three day weekend with coworkers so I could be on this snowmobile trail in the fading light and dropping temperatures.

It was a six mile ski to Slavonia, started at 3 p.m

Occasionally, I moved myself and the whole rig out of the trail to make way for the snowmobiles, so I could breathe their exhaust fumes for the next couple minutes. The demented yowling of their engines bounced off distant ridges. To be fair, this trail wouldn’t have been here if not for the snowmobiles, but I was proud that I was planning this trip motorless from doorstep to mountaintop.

The pulk skittered over the broken snow crust behind me. Going uphill with this thing definitely upped my calorie consumption; going downhill with it boosted my adrenaline. I poled frantically to keep the fast-descending object from swinging in front of me and knocking me off balance.

The fact that I’d attached the sled to me with stiff ski-poles instead of rope meant that at least I didn’t have to worry about it taking me out at the legs.

Fears about whether I could really make the homemade pulk work had been among my doubts about whether I could pull off this motorless expedition. I was thrilled to see that I could move everything smoothly enough

Tomorrow, I’d get to have all the weight on my back, and hopefully be able to haul it all uphill through deep powder to Mica Lake. The third day, I planned to go on with only bare essentials in my backpack. If I could steer clear of avalanche zones and fatal rock precipices, I could reward all these efforts with a smiling moment on a mountaintop.

It was dark by the time I pulled into Slavonia. The small wooden structure at the edge of the parking lot looked far more inviting than the tent I had yet to pitch.

Yes, that small building happened to be the trailhead bathroom, but so what? The shit was frozen anyway.

I wasn’t out to get the glamorous camping award, and if this saved time from taking the tent down in the morning, I was all for it.

Another perk: I could set my stove up inside to cook dinner. I locked the door to offset the slim possibility of someone making a late-night visit to the facility. I later noticed a sign forbidding camping in the area. Well, lest I paint myself as a scofflaw, let’s just say that I was taking a very long dump, a dump that happened to last until the morning.

When people wake up on a bathroom floor, it is usually the product of hazy decision-making half-remembered, if at all. In this case the bathroom floor was a key part of my plan to make up the most distance possible the following morning.

The morning still sucked, as mornings winter camping will suck.

Sure there’s the beauty of the silent world, the promise of the untrammeled snow. Also there’s the numb fingers, numb feet, the intrusion of dampness where you don’t want it, the burden of leaving the marginal comfort of the sleeping bag for the thousand little camp tasks and packing.

There were no tracks on the trail, leaving me to break the powder. I’d left the sled behind — it’d have been useless in this stuff.

Leaving the skis behind had been the difficult decision. Even if I’d put climbing skins on the bottoms, I knew that I wouldn’t be able to make the same time that I would make in snowshoes. Strapping them to the pack would have added bulk to an already mighty load, and probably would have gotten tangled in trees on the climb up. It would have been hard to get a slick ride down with all the weight on my back anyhow.

My goal was the mountaintop, not a flashy descent. With skiing out of the picture, I could focus on tasks like route finding.

Locating the trail under the feet of snow in a willow drainage was no easy task. I meandered through the aspens in the valley, staying on an eastward course. I used my topo map to find the drainage between two mountain ridges that was my golden ladder to Mica Lake.

Finding the route and climbing it are not one and the same however.

My snowshoes, which are great for floating on loose powder, are less awesome on steep pitches. I found myself doing elaborate traverses, pulling myself up on tree trunks. This was a dangerous game because said trees were loaded with beachball-sized snow bombs, quick to drop when shaken. Sometimes the trees would drop their payloads for no good reason and white powder would explode over my head and shoulders.

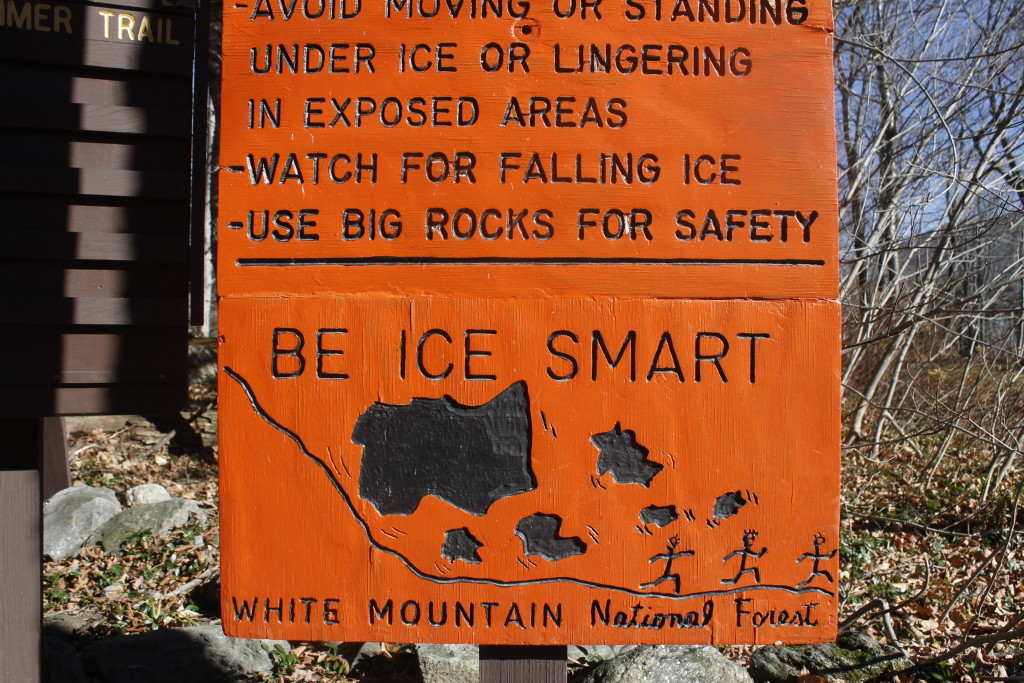

The other kind of falling snow that I worried about was avalanches. Sources had told me that the east side of the valley was dangerous (windblown snow would accumulate on the west faces with the prevailing wind) so I tried my damnedest to stay on the opposite side of the drainage.

The task was not so easy because of Mica Creek, which sometimes cut up to 30 feet down into the bedrock. The topography in the basin forced me to cross the creek several times — walking oh-so-delicately over the snow bridges.

The water might have only been a couple feet deep, but if I soaked a boot, I would most likely have to turn the trip around.

There was also no easy way to get down to the water without falling into it. I refilled my water supplies by dangling a bottle off a cord from one of the snow bridges.

A narrows lay ahead, which included a steep climb between two steep snow-covered walls.

Here, the safe west wall had the most evidence of falling snow. However, the drop wasn’t so long and I didn’t worry about a light snow sloughing going over my boots. Nothing that I could see had fallen off the other side of the canyon, but if something did fall, it could have made for a minor avalanche. I stayed west.

At the top of the narrows, the drainage opened up into a valley. It was maybe half a mile wide, flanked by razor-like mountain tops.

The drainage forked and I chose to go right, climbing up a steep ridge between Big and Middle Agnes. Few trees grew on the high snow fields. Eventually there were none, just blank white snow and jagged rock. I scanned for a route that would keep me out of avalanche danger, but also keep me away from impossible rock spines and other hazards.

Two ominous tracks of busted snow streaked several hundred yards down the south face of Middle Agnes. Avalanches had fallen here.

The more I climbed, the more I expected to run into Mica Lake. Eventually, I realized that I had gone way too far to the east, and turned back downhill.

Water, food and warmth were the three priorities on my mind as I came into camp.

Light was already fading by the time I reached the lakes’s edge, meaning I had to hustle to do my chores.

I used my ice axe to bash a hole in the lake ice and get water (difficult because there was only a couple inch margin between the ice and the lake bottom). I climbed a slight hillock nearby where I dug a large pit in the snow where I pitched tent. I got another pit started for my fire.

The axe came out again for fuel gathering. I swung away at the spruce branches nearby by the light of my headlamp.

I took one mighty swing at a branch only to have the axe fly out of my hand. I heard the familiar, musical dong! as the axe bounced into something nearby. But where the hell did it land? I swept the snow and the tree branches nearby and found nothing. I tried recreating the trajectory of the lost axe by throwing sticks and seeing where they landed. Eventually, I dug around through the powder with a stick and still came up empty. I called off the search after a half hour and got to fire-making.

Say what you will about the romance of woodsmoke rising up in cold winter air, I’d have probably just used my cookstove if I’d known what a royal pain the campfire was going to give me.

I had some Vaseline-soaked cotton balls with me, excellent fire-starters, but my supply was low, and I decided to save them for an emergency.

Another challenge was that the lodgepole pine didn’t grow up here. This meant that I no longer had the ubiquitous, highly flammable, red needles that I’d used to start fires easily at lower elevations.

I tried lighting notebook paper and drier lint that I’d brought with me. The licks of flame rose like a promise — and sputtered out as I hacked smoke. Finally, I broke off a piece of candle and added it to the lint. When the lint ignited, the burning wax kept the whole shebang going long enough for me to ignite some dead spruce twigs.

Cooking on the wood fire was like getting teargassed. Every time I reached in to shift the pot over the flames, I got a throat-wracking, eye-burning draught of smoke. By the time I’d softened the lentils enough to be palatable, I had a dull headache and a sore throat.

I ate as quickly as possible, as the fire wound down. I put another pot of water on to pour into my metal bottle to heat the foot of my sleeping bag.

I had put spruce boughs under the tent for extra insulation against the cold. I propped my backpack under my sleep pad, and put the sleep bag into an emergency bivvy. I felt confident that I would be warm enough this evening. What I was having a hard time imagining was getting up at 4 a.m. to fetch water and prepare my gear with numb fingers and toes. I knew it would be best to get up early if I wanted to do anything before the snow softened, became harder to walk on, and more likely to avalanche

I dreamed that I woke up in a blizzard, with snowmobiles wheeling around camp. I hated that the whining machines had made it to the lake I had worked so hard to get to on my own, but the falling snow meant that I probably wasn’t going to try the mountain. This thought felt like a relief.

I woke up at 3:49 a.m. thoroughly confused, unzipped my tent to look up into a clear, cold sky. Stars glittered like ice shards on black water. A crescent moon cast its pale light upon the snow world.

Body and mind might not have been motivated, but my bladder had a strong motivation of its own. Once it had motivated me out of my sleeping bag, the hardest part was over.

I decided to pretend that I really was stoked that I was getting up this early. The fake motivation helped me to wrangle gear together, strap snowshoes on my boots and trudge down to the ice hole on the lake to fill water bottles.

Fortunately, I’d put snow back on top of the hole after I’d filled up the last time. This insulation had prevented the ice from completely reforming. I was able to bash the hole back open with the tip of my ski pole and a liberal dose of profanity. The water was slushed with ice shards. It would refreeze quickly in the cold air. I put one bottle in my pocket and stuffed the other two into my jacket. In this way, I kept my water supply close to my body heat.

Unmotivated to start any fires, I opted to skip the hot breakfast for a Clif Bar.

As soon as all the camp duties were over, it was almost 6 a.m.

I retraced my snowshoe tracks to the basin above the lake and then chose a route going up a valley on the south side of the mountain.

The world was painted in deep dark blues and the pale hues from the moonlight. In a world that seemed half-real, the cold felt real enough. I had the iciness of the water bottles near my skin, frigid air moving through my nostrils. Movement was the way to stay warm now that I was out of the sleeping bag. As I toed up the first snowfield, the sense of purpose that I had been faking earlier began to gel into the genuine object. Movement was what fought back against the vulnerable feeling walking alone in cold darkness.

I knew my confidence would grow when the sun came out, and that I would be glad that I decided to begin this early hike when I had the chance. I knew that I had already invested a lot in this hike, and that if I backed down, it would be hard to rally the courage or the fortitude needed for future adventures, and that I would be giving up on some of the qualities that I value most in myself.

One shooting star raced across the sky. Another flicked by a couple minutes later. Then there was another, and another.

A set of lights from the distant town of Clark twinkled far below. I raised the climbing bars on my snowshoes for extra support as the route steepened.

Paranoia about avalanches kept bubbling into my consciousness.

I kept inside the trees as much as possible — there was less likely to be snowfall there. I inspected the tree trunks for broken branches or snow accumulated on the uphill side.

I topped out on a sinuous ridge of snow, walked the edge down into a treeless basin. A dim green glow gathered above the ridge-line to the east.

Avalanche-wise, two factors were in my favor: there had been no new snowfalls in the past couple weeks, which meant that the snow that was on the slopes had had time to stabilize. Also, it was still very early in the morning, which meant that the snow was far more stable than it would be in the afternoon.

Looking up at the face I planned to climb, I could see no avalanche tracks. Still, I planned to weave around as I climbed to avoid the steepest pitches and to move in the shelter of some boulder-fields. If things began to look truly sketchy, I’d turn around, I promised myself.

Climbing the steeper pitch in my over-sized snowshoes did turn out to be a challenge. I found myself sliding back at least half as much as I could step forward.

Finally, I swapped out the snowshoes for crampons. The crampons gripped exquisitely, but didn’t do jack to keep me from falling through knee-deep snow.

I leaned forward into the slope so I could put more weight on the ski-poles — even flopping them flat onto the snow in front of me like some bizarre climbing flipper. I approached the top in this awkward crawl, suitable behavior for a supplicant. Now and then I looked out or down. A radiance swelled above the eastern ridge. The sky went from dark to gray. I watched as first sunlight burned on the high peaks, marching like fire down the slopes to ignite the darkened world below.

The pitch got steeper and steeper. My heart beat like crazy as I fumbled along. I got to a second set of boulders and jabbed the crampon points into the rocks to haul myself up. The thought of avalanches reverberated through my brain. Was this snow too steep? Should I head back. The snow was getting crustier here. I watched tiny snow chunks dance out from beneath my crampons and roll, roll, roll, roll, down the hill, leaving particle accelerator tracks in their wake. One chunk of crust wheeled down the mountain like a runaway buzzsaw

.

When I tried to kick out some larger slabs, however, they only went for a couple feet before they stopped. The slope seemed too gradual and the snow too cold to really rumble. I still felt unease in the pit of my gut. My awareness also went to my right foot, which had gone numb with cold despite the climbing workout.

For the last forty minutes, I’d had my eyes set on a leaning boulder, that was higher than anything I could see on the mountain. It had seemed like only a quick jaunt to get there, but my approach was painfully slow. I struggled to lift the crampons above the crust so I could fall back into it. I worked my fingers into tiny holds in the rocks in order to flop myself over. I stumbled, drunken to that ridge, looked out and gasped.

I’d gone from looking ahead inches past my nose, to looking out over unfathomable miles. Boulder projections stabbed the sky off knife edge ridges. They glinted in the orange illumination. The Zirkel range rose up in a defiant bulwark on the other east of the valley. Further south, mountains followed mountains like shark teeth. There was a gap at North Park, on the other side of the Continental Divide, and then the mountains rose again. Miles of empty table land lay to the north in Wyoming.

I instinctively recoiled from the edge. Indeed, I could see places where cornices of overhanging snow dangled over the the cliffs like trapdoors to the abyss. I could also see, unhappily, that there were two other peaks on the ridgeline before I truly reached the top, and these peaks were separated by a narrow, dangerous-looking ridge with a thousand-foot drop on either side.

“Well screw that,” I thought.

I turned around and began tramping down the crusted snow.

At one point, I heard a rumble overhead and my heart lurched.

I whirled around to realize that it was only an airplane.

Another glance at the snow face, made me reconsider the avalanche danger. I took a slope measurement using a trekking pole and a compass as a protractor. I estimated that the slope was only about 30 degrees, if that, which was about the least steep angle that an avalanche would happen.*

I also saw that there was a way to cut to the west side of the summit ridge, which might take me to the highest peak while avoiding a walk on the knife edge.

I had already committed 20 minutes to walking down the ridge and it would take a lot longer than that to get high again. After standing in place for a minute, I started trudging back up the way I’d come. It was far easier going up the already broken snow. Finally, at a boulder-field just above the summit, I made a dogleg to the west. Again, I stuck crampon points against hard stone. I maneuvered around the first peak and over to the second. I topped out with another view into the vast gulf stretched out to the north of the peak. The third and final peak was maybe two football fields away.

But the knife edge was even sharper between these two peaks, and if that wasn’t sketchy enough there was a tall vertical rock outcrop standing right in the middle. Climbing over wasn’t even a possibility.

If I wanted to get beneath the outcrop, I would have to crawl out onto one of the absurdly tilted snowfields on either side. If my crampons could grip into the champagne powder snow and my hands could grasp some tiny chink in the slippery rock, I could see a minute chance that I could crawl out to this final peak. But when I tried to visualize this possibility, what I saw was a tumbling, thousand-foot death ride that got faster and faster until that sudden stop at the end.

I realized that I had to turn around again, just a couple snowball throws away from the summit. Knowing that I had exhausted all my options, made it easier to turn around without pesky second guesses to haunt my descent.

It is likely that if I had gone the standard summer route, approaching the peak from the east side, that I might have found a way to this final peak. Then again, going this far to the east would have added many miles of unbroken powder to my trip, and for all I knew, there may have been avalanche risk that would have fudged my chances there.

Half an hour into my descent, I was close to the shadow of the ridge line, where the sun still hadn’t risen. I crouched in the shelter of a boulder so I could swap out my crampons back into snowshoes where there was solar warmth. This was where I discovered that the water bottle in my right pocket was empty. Where had the water gone? Mostly into my right boot. No wonder why that foot had been so cold.

It was my fault. When I’d filled the bottle in the slushy water, there had been ice crust on the screw threads and I had failed to twist the cap all the way shut.

I squeezed out of the sock and set it in the sun, warming the foot as best as I could with my hands.

It took another hour and a half or so to get back to camp.

I’d knocked out the fulfillment part for this trip’s hierarchy of needs (OK, almost fulfilled them. I didn’t quite reach the summit did I?) now it was back to basics: water, warmth and food.

It was a beautiful sunny day on the snow and I felt no need to hurry back down to Slavonia for another night in the bathroom. It was nice to take care of camp chores at a leisurely pace.

I walked out on the lake ice to where I found a mushy patch near where a stream came in. I was able to use my snow shovel to dig out a generous hole to fill my bottles. I took the rainfly off my tent so that the sun could burn away the humidity, and threw my damp sleeping bag over a spruce sapling.

I had snagged some dead red needles on the way back to camp, which I used to set a new fire on my cook-pot lid. My boots hung out on sticks jabbed into the snow, so that the most amount of warmth could get into the toes. After a while, I started some pasta mixed with coconut butter. I was out of patience for the slow-cooking lentils. I watched the steam rise from my boots and socks. I put my metal water bottle near the fire so I would have something hot to put in the toe of my sleeping bag.

It would be a good night’s sleep.

* https://utahavalanchecenter.org/blog-steepness. Here is one source, amongst others that explains the relationship between slope angle and avalanche risk. Though this blog describes me doing my best to use what I’ve read and picked up from others to stay out of avalanche danger, I haven’t taken any classes, and don’t want to give the impression that I am an expert on the subject.