Going beyond the tent

Building shelter is one of those challenges that isn’t necessarily easy in the backcountry, but like starting a fire, gathering food or navigating off trail, it offers its own satisfaction.

We seek empty spaces as a way to commune with nature; what better communion than to sleep in a dwelling made from the elements of nature?

In the Routt Mountains in northern Colorado, the element I notice above all others is the several feet of snow on the ground, snow that an enterprising adventurer could stack, sculpt, or burrow into for warmth. The air trapped within creates insulating properties that my three-season tent doesn’t have. Plus, the snow is already there. I don’t have to haul it in on my back to make a home out of it — though a snow-shovel can be helpful.

So why have I bothered lugging my tent along when I go on a multi-day trip when I could build a better product out of snow? The fact that I can set the tent up in minutes rather than hours has something to do it. Then there is that fear that I could screw up at shelter building with no recourse except a night in the cold fury of the elements.

Therefore, when I decided to try my hand at igloo building, I chose to erect my first shelter up on a ridge, maybe a quarter mile away from the very solid, timber-built, central-heated structure where I actually sleep most nights. If I screwed up here, a warm bed would be just down the hill.

Champagne powder into snow boogers

I should make a note about what I’m talking about when I’m talking about igloo building.

When I tell locals that I’ve built an igloo in the woods, they will often ask if I have actually built a quinzee. In order to build this kind of structure, you build up a big mound of snow and dig it out. My dad and I built quinzees during some of Connecticut’s epic snow years.

To build an igloo, I planned to take blocks of snow and raise them up into a dome. Blocks of snow? This seemed impossible for this part of the Rockies where the snow has the consistency of baby powder.

Snow is a malleable medium, however.

I stumbled upon a eureka moment on my trip to Big Agnes in early January. While digging a pit for my tent, I could shovel snow out in large chunks if I went over it in snowshoes first and left some time for it to set up. The chunks weren’t blocks per say; they were more like irregular snow boogers. Still, I started thinking that these boogers might make a viable building material.

If I could build a shelter with this stuff, it would be a cheap alternative to an Icebox, which is an igloo making device that a Colorado company makes. I had pondered buying one of these so that I could leave my tent behind on trips. That said, many reviews I read online reported that it still took four hours or so for them to put the igloo together. Craig Connally, author of “The Mountaineering Handbook,” says it only took him two hours to build a decent structure. Connally, advises mountaineers to eschew four-season tents when there’s snow on the ground, and get an Icebox instead. He argues that there will not only be a weight savings, but also a time savings.

“Remember,” Connally writes. “…the people who spent the night in their tent will have the pleasure of digging out the frozen anchors, attempting to dry the frost and condensation in the tent, and packing the frosty tent away with a little extra weight to carry.”

This endorsement had me close to buying an Icebox, but then I started thinking that I might be able to build an Igloo without one if I compressed the powder with my snowshoes.

A week after I got down from Big Agnes, I went on a shorter trip up the ridge behind my living quarters. I scouted out a horseshoe-shaped ledge in the hillside where the snow was deep and the firs grew tall. This place would be in the shade most of the time, meaning colder nights, but also a longer lifespan for any structure that I built.

I started tromping circles in the fresh powder, pressing it down toward the earth. After I had compressed it to the max, I took my snowshoes off and started packing the snow in boots alone. I left to grab lunch, then came up a few hours later.

Working with the snow shovel, I dug out beachball-sized snow boogers and arranged them into a horseshoe about six feet in diameter. I kept building until the walls were about belly high. Then it was time to go in for dinner. I stomped out more powder so that there would be more building material for the time I came back.

Putting it together

I came back about a week later with my canoe paddle.

I’d just hauled the kayak to the top of the ridge and planned a to go for a fun-filled descent later on. In the meantime, I tried using the paddle to stab out snow blocks.

It turns out that the flat blade was able to extract a much better product than the curved head of the snow shovel. Most of the blocks were still irregular; a snow saw, the kind used by actual arctic natives, no doubt would have been the best tool for the job.

I compensated for my goofy building blocks by mortaring gaps with broken chunks of snow and loose powder. Snow is awesome to build with when you consider that you can squash different pieces together and make it one whole. It forgives plenty of mistakes.

The part that made me nervous was leaning the walls together. I had visions of myself cursing over the collapsed walls. Due to my reluctance to lean the blocks, the igloo was becoming more cone-shaped than dome. My early plan had been to leave one gap in the walls so that I could walk inside in order to lean the top blocks together to create the ceiling — but this wasn’t working. The gap made the whole structure unstable. I had to close the ring, and dig my way in later so I could put the top pieces on.

When the walls got above shoulder height, I started scooping snow around the base, creating a step ladder from the powder so I could put the top blocks in. This fresh snow (I hoped) would also reinforce the walls for the big hole I was about to cut in the side.

I planned to dig under the walls as much as possible to avoid compromising the structure. There was maybe three feet of snow between the bottom block and the dirt. I started my burrow a couple feet away in the already-packed snow, making a mini-quinzee for the igloo foyer.

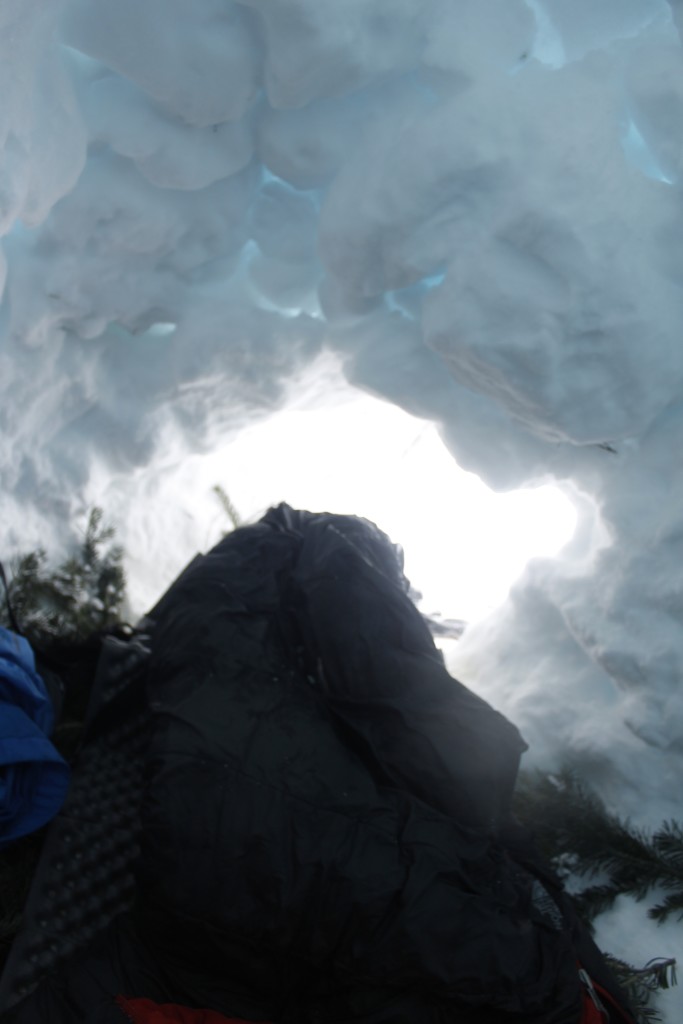

It took me about half an hour to stab my way through and excavate the rubble. I crawled through the tunnel to the cold blue sanctuary within. There was a manhole-sized gap in the ceiling — the last part of the job. I dug some boogers out of the hardpack beneath my feet and then I was closed in.

There was just enough room to stand, and I could lay flat with my feet jutting out into the entrance tunnel with room for a guest (but let’s not get ahead of ourselves here.)

The insulated walls created a stillness. It was calming to sit in the soft blue light coming in through the cracks between the slabs. It is that same calmness that follows a face-plant skiing. For one cold moment, you look down into that cold, still world beneath the snow, a place which is devoid of the noise and motion outside.

“I could stay here, a while” you think.

I spent some time filling in cracks with snow mortar. Then I went outside and broke a mess of branches off from a nearby fir tree. The flat needles made a perfect floor for my new dwelling.

I decided to leave the structure up one night to make sure it wouldn’t fall down for no good reason. Assuming this wouldn’t happen, I planned to spend the next night in my very own snow booger hotel.

Sleepover

Pale moonlight filtered through the snow clouds as I tromped my way along the pathway up the ridge. Cold flakes melted on my brow as I climbed. A hush on the land. No wind.

From the top, the far flung points of orange light from different houses in the valley looked like ships on a dark sea. A leather slap beat of cowboy boots on hardwood echoed from a barn dance below, but I was in no mood to fumble through a botched set of promenades and dos-i-dos.

The noise faded as I retreated through the pines — the dark deep realm that seduced Robert Frost one snowy evening.

My igloo entrance beckoned out of the from gray snow. I got on hands and knees to crawl through to the womb I’d built for myself.

The scent of the fir boughs lent their crisp scent to the still air. Within minutes, my body warmth boosted the temperature inside my dwelling. I blocked the entrance with my backpack, zipped into the sleeping bag.

I kept the snow shovel close to my head just in case I needed to dig myself out of a collapse.

As my eyes adjusted in the dark, I could see the gray outlines of the blocks I’d built for myself. The ghostly, non-uniform shapes made good dream food.

I slept deep.

The next morning, I checked the water bottle I’d left next to the sleeping bag. No ice whatsoever, though the weather service had predicted the temperature would be 17 degrees that night. An inch of powder had fallen outside. I took a sled ride down the ridge and got to work on time.

Some notes on snow building

I call it a snow booger hotel. Others might call it a rubble hut. I call it an igloo sometimes, but I know that I didn’t build it with the same craft as a true igloo. I guestimate that I spent about eight hours building the thing but I wasted time with a few mistakes that I wouldn’t repeat on a second go round.

Could I use something like this on a real trip and leave a tent behind? I’d be willing to try as long as I had a backup tarp, no bad weather was moving in and I got to camp by noonish.

One mistake I made in this project was that I spent way more time packing snow more than I needed to at first. I’ve found that tromping over the snow with snowshoes a few times with the snowshoes and waiting 10 minutes is a viable way to get snow chunks. I’ve also been able to dig up juicy chunks out of the half-melted snow near fire pits. Areas of wind-blown snow could also work (similar to what the arctic people would use to build) because wind will shatter snowflakes and create a denser medium. Snow that’s also been in the sun would also work. When I was camping at 10,000 feet the snow was deep enough that some of the bottom layers were naturally chunking up, but the base isn’t quite deep enough to get those benefits at my current elevation.

I dug some OK chunks out of a groomed snowmobile trail as an experiment. Building a snow shelter this way will make some snowmobilers unhappy, but in a survival situation…

I also built this snow shelter much larger than I needed to for strict survival purposes. If I did build something out on the trail, I would build a lower ceiling to save time and allow more room for warmth to accumulate. The shelter did sag a bit after a couple days, probably because my dome was sloppy, but I reinforced it with more snow and it seems OK so far.

Digging under the wall as opposed to leaving a gap in it throughout the building process worked well for my purposes.

I’d like to try using my stove or a candle inside to see just how well that works to warm the whole structure. Another challenge would be to see how well I could compress the snow for block making if I were using skis instead of snowshoes.

As for whether I will buy an Icebox, there is no question, that the product makes a better looking product, and I could probably build an igloo faster if I had one. I’m going to save my money though.

Considering how much snow is lying around northern Colorado, it might be fastest just to build a snow cave or a quinzee in order to make a shelter in a pinch. I’d like to try both before the winter is out. I’ll let you know how it goes.